The Broken Triangle

If you’ve ever worked in a large organization, you’ve probably wondered from time to time, just what the heck they’re smoking in the C-Suite.

If the vision, goals and objectives at the top of the house were crystal-clear to everyone, we wouldn’t have so many misfires at the Dilbert level.

Why is this? What can we do about it?

We can talk about any number of reasons. Things like, “The folks in the trenches don’t have to worry about the big picture the way we do.” (Counter: “The folks upstairs don’t have to sweat the details the way we do.”) Or “The little folks aren’t looking toward the future the way we are.” (Counters: (1) “You’d be surprised.” (2) “The big kids have no idea what they’re asking us to do.”)

You get the idea. Add to this the temptation to discard what we were doing last year in favor of what we need to do today. After all, life is ever-changing, isn’t it?

So we try to solve it through communication. Communicate fast, early, often. But exactly what are we communicating, and why? And are people really hearing, embracing, and acting on the message?

Let’s tackle this by examining how things tend to work in a large organization.

First, what do we expect the C-Suite folks to do? Well, for starters, look toward the future, determine trends, environmental changes, competitive direction, opportunity, risk, etc. In other words, assess.

Next, C-Suiters compare their assessment to the organization’s present goals. Are those goals still valid? Do they need adjusting?

At this point, goals affirmed or adjusted, C-Suiters choose ways forward among alternatives — strategies. This is tougher than it sounds, because (as Richard Rumelt has argued), if your strategy hasn’t caused pain somewhere, it isn’t a solid strategy. Choice is difficult. Some people lose. Others win. Ultimately, the courses chosen are fashioned for the good of the organization — and its people, however bruised some of them may be.

Now, all this sounds noble. And some of it rightly takes place behind closed doors. It results in a C-Suite-developed set of goals and strategies to move the organization forward.

That’s hardly the problem. The problem is, who knows about this, how much can they know (some stuff is confidential), and how do we help them figure it out?

The Broken Triangle - Version One

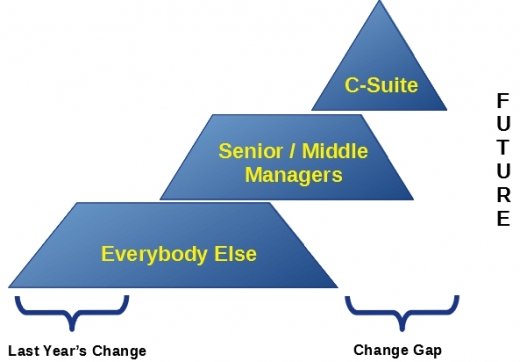

For this, I’m going to ask you to consider a simple drawing - a triangle cut horizontally into thirds. This is pretty standard. The top layer comprises the C-Suite. The middle layer comprises management. And the lower layer comprises the rest of the workforce.

Sounds like a valid model for the organization, right? The problem is, it’s wrong. Here’s why.

Here’s what’s really going on, when we apply a time scale:

The C-Suiters have just spent a boatload of time figuring out alternatives for the future, involving some of their senior and middle management teams. If they’re smart, they’ve also solicited opinions from a lot of other folks throughout the organization, incorporating intel from the front lines into their decisions. Even with all of this, the upshot is that the C-Suiters have moved their thought further into the future than some of their managers and most of the rest of the organization. This leaves them in a situation where they now need to figure out how best to communicate vision, goals, and strategies to everyone else, and do it in a simple enough fashion that people can get it. (Whether the people respond or not is a separate question.)

If the result of all this effort is the broken triangle I’ve illustrated, then why not bring everybody along for the entire strategy formulation journey? In other words, prevent the triangle from breaking?

Two reasons.

One, a whole lot of people need to feel they are contributing to the organization as it is, doing the work that’s been laid out in front of them. This is not patronizing by any means. Instead, it recognizes that people feel valued when they know their contributions are making a difference. That’s real work, in the real world, the real here and now. And it’s incredibly valuable and needs to be rewarded as such. Pulling people from this work and asking them to join in what can be an arduous and lengthy exercise is work on top of work. Sure, some will do it - and these are folks you want to put on your strategy team. But they still represent a tiny fraction of the “Everybody Else” section of your organization.

Two, to paraphrase Bismarck, a lot of strategy formulation is like making law or sausages: You really don’t want to see it being done (1). The hurly-burly of this effort can be daunting; moreover, when people are confronted with the uncertainty attending this kind of decision-making, they can become very anxious. So only those folks resilient enough to assist in your strategy formulation are best equipped to play in this space.

So that leaves us here:

Not only will the bulk of the organization be struggling with the changes the C-Suiters are trying to put in place, it will also be struggling to assimilate the last set of changes that, for last year’s good reasons, had been initiated. Trying to push on the left side of the base, or even the middle, gets one nowhere.

The Broken Triangle — Version Two

I discussed this first version of the Broken Triangle with a senior leader of a multinational corporation. He had a different perspective. He suggested that the lowest part of the triangle was actually farther to the right than I had illustrated above, and that it was the middle triangle that seemed to be farthest to the left, like so:

This leader said that when he spoke directly to the working level (I.e., in skip-level meetings), those folks grasped and generally supported the vision. It was the middle layer of the organization that seemed to have the most difficulty. Why was that, and what could be done about it? It turns out, there are many tentacles to this issue — which makes it all the more important to address and work to resolve.

That Stubborn Middle

What is it about this middle layer? It’s been called the “clay layer” — ideas and issues percolate in from top and bottom, but almost never pass through. Many very capable people occupy this level, and many of them can be frustrated and, at times, downright weary and even unhappy. Who can blame them? How would you like to be referred to (at least indirectly) as the level that inhibits progress?

What’s going on here? (2)

People in this middle wedge — mostly mid- to upper-level managers — experience multiple pressures. I call these business crosswinds. Here are a few:

Coaching and guiding their teams, while handling challenges from other organizations

Providing status to their management, and performing course correction

Supporting various company activities - budgeting, forecasting, personnel development, etc.

This is an easily expandable list. While people at all levels may recognize the pressures on the folks in the middle, very little is done to address them. When we speak of bureaucracy in organizations, a lot of it tends to coagulate here. As I’ve said elsewhere, bureaucracy is the strangler fig of your organization. Addressing this issue is key to containing that company strangler.

But this is easier said than done. A key reason is that managers live in a world of competing value streams. (That’s a topic for a separate exploration.) Briefly, managers are balancing all kinds of transactional activities: How to satisfy the latest cost-cutting initiative; making sure their people sign up for the new mandatory security training; determining when a key person on the team can move to a new career-enhancing position, and figuring out who can help interview potential replacements; resolving a conflict among team members; resolving a conflict with another department; filing the monthly budget performance report; answering an HR survey regarding key talent; keeping an open-door policy and managing one-on-ones with subordinates; providing input into the next department meeting; preparing for the next leadership offsite.

That’s just off the top of my head. (I was a middle manager once; can you tell?)

Who’s got time to do any visioning in that environment?

And in big organizations, climbing the ladder to middle management can take time. Along the way, managers-to-be are identified and rewarded for behaviors that suggest they will one day be effective managers. Measuring. Maintaining. Delivering. Coaching.

In rare circumstances, we may reward visioning.

We reward managers precisely because they excel at managing. They work in a world I call the certainty box. The certainty box contains budgets, resources, competing departments, goals and objectives, crises of the day — in short, everything that makes a manager’s job challenging, time-consuming, and draining. What the certainty box doesn’t contain a whole lot of, is vision. Nor does it allocate much — if any — time to such exercises. (More on the “certainty box” in another exploration.)

It takes a rare kind of manager to set aside all the concerns of the day and find a way to participate in, or at least respond to, direction setting of the leadership team. So while the worker bees may “get it” (especially the younger ones, who likely comprise more of the bottom triangle), middle managers have been around long enough, been bruised enough, can see the downsides, and are so overwhelmed by the day-to-day that they find it hard to tilt their chins high enough to embrace the art of the possible.

And there’s this. Consider how you hire into your organization, and how you develop your people. It may just be that you concentrate your external hiring practices on new recruits — after all, you need a steady pipeline of new talent. You may also look externally for high-profile senior positions — people with proven leadership credentials who can inject new leadership practices and new vision into your organization.

What are you doing for your middle level? Most likely, promoting from within. After all, one of the recruiting strengths for any organization is a demonstrated path up through the organization. Add to this the signals you send regarding what gets rewarded. The interplay between risk, culture, performance management and upward mobility — leading to internal debt — is much too large to explore here, even as it contributes to this challenge.

There is one last factor — and it is an extremely sensitive one, so I’ll tread carefully. If you have promoted from within, odds are the demographic of your middle layer is populated with people who have quite a few years’ experience in your organization. This demographic must not be construed as age discrimination, with all the alarm bells that that should rightly trigger.

What is at play here — when we look at the aggregate, as opposed to the individual — is a population that likely has deep roots in two soils: (1) the cultural soil of your company; and (2) the compelling soil of their community. This means that they may be unwilling to move, either culturally or physically. The first contributes to the stubbornness of this layer, while the second creates challenges if you’re trying to inject fresh insights from outside.

So, here is what we have:

Crosswinds and bureaucratic drag

Transactional activities

Certainty box rewards

Barriers to entry for new ideas

Here’s a final teaser: How much of this exists in large, established organizations, versus newcomers? How much is a function of size, or longevity? How do past experiences, such as internal failures, product liability lawsuits, public relations fiascoes, and the like, contribute to this stubborn middle? And is this why many organizations study lean startups (or upstarts), looking for fixes?

The stubborn middle is a huge challenge. What to do?

Realigning the Triangle

When I first conceived of the broken triangle, I only had Version One in mind. For that version, these suggestions might work. Doubtless you might add more or take issue with some of them:

Simplify the message: Provide clear goals and outcomes, plus phrases everyone “gets” and can rally around

Tell stories: Celebrate successes, however small, that show how the new vision is taking hold; try to win the hearts of your people through examples lived by folks just like them

Use feedback loops, ropes and ladders: Provide tools to help people express concerns and find help and encouragement moving in the new direction

Acknowledge FUD (Fear, Uncertainty, Doubt): Recognize as natural to the change process and take steps to alleviate

Find silver linings: From failures come sharable learnings, and some failures can be celebrated — even failures at the leadership level

Respect conflict: Through conflict come some of our best ideas — especially conflict as people discover violent agreement with the values beneath the vision

Measure carefully: Look for success, but without burdening the organization or penalizing the status quo (because some status quo is needed, even during change)

Adjust performance assessments: Carefully build in vision-supporting objectives (and beware of implicit penalties for honest mistakes, slow uptake or well-reasoned challenges)

None of this is easy — and, truth be told, I thought organizations had their hands full just dealing with Version One issues. After all, these things are really hard work, and they have to be built into the vision investment model. It’s all meta-work — work about work — but some meta-work is needed for success.

Now let’s tackle Version Two.

Remember how different software packages are advertised? For Version One, you get all these features; for Version Two, you get everything in Version One plus all this other stuff? Well, I’m afraid that’s the reality here as well.

So, in addition to the actions for Version One, buckle up and buckle down on these suggestions:

Identify and reduce crosswinds: Find out where the biggest crosswinds are in your organization, and take these steps to address them:

Use lateral communications: Especially important if yours is a major functional vision and strategy versus a corporate one; you must ensure that communication flows across the organization, as well as vertically

Use moccasin walks: I coined this term to refer to “walking a mile in the other person’s shoes” (2) — not only vertical walks, but also lateral walks; these promote empathy and understanding of often conflicting perspectives, and a way forward to resolving them

Balance transactional activities with vision-supporting activities:

Root out non-value-add (NVA) meta-work: Easier said than done, and you must handle carefully through skills transference (because even NVA work is meaningful to those performing it);

Carve out and enforce time to be spent learning about the new vision and strategy, using feedback loops

Complement certainty box awards with uncertainty exercises:

Use stripeless meetings, scenarios and future stories exercises to tip up the chins of your highly valued, smart and experienced managers

Look for ways to streamline and consolidate certainty measures, balancing them with rewards for more visionary endeavors

Breathe more life into the middle layer:

Use lateral (cross-functional) brainstorming sessions to generate new ways to support existing and visionary work

Carefully adjust staffing practices to provide pathways for outside influencers and younger talent, while respecting contributions and aspirations of your experienced folks

Summing Up

I’m sure there’s a lot you could suggest, and plenty of challenges to all these suggestions. I am, after all, only one person. While I’m committed to finding ways that help organizations improve, I’m also finding ways to self-improvement. Especially when it comes to tackling tough subjects like this one.

If nothing else, this long journey may provide you with food for thought. Perhaps it may spark innovative approaches you can take to attack this fundamental broken triangle issue. I’m open to suggestions and criticism. Above all, I hope that in some small way this has helped you see this issue in a new light.

Thanks for going on the journey; until next time.

_________________________________

In one of those bizarre things you learn when double-checking your research, Bismarck never referred to law and sausages together - even though it’s been attributed to him since the 1930’s. The earliest quote is from John Godfrey Saxe, an American poet, who in 1869 was quoted thus: “Laws, like sausages, cease to inspire respect in proportion as we know how they are made.” … I suspect, given that mouthful, and given that (a) Most people know who Bismarck was and (b) Most people don’t have a clue who Saxe was, the quote received what today might be called an extremely slow-motion mashup. It became “Laws are like sausages. You should never see them made.” And attributed to someone well-versed in both law and war.

Whenever I use this phrase, I think of the first professor I had in my MBA program (Dr. Krachenburg — also dean of the school of management), who, in our first org behavior exam, provided a story problem and then asked the first question: “What’s going on here?” Since that day many years ago, I came to understand that Dr. Krachenburg echoed what Richard Rumelt has said about strategy: a whole lot of it is just figuring out what’s going on.

I first heard about this as a Lakota saying, but it turns out that this is wrong — while many people have attributed this to many different indigenous tribes, it’s really from a poem — see https://www.aaanativearts.com/walk-mile-in-his-moccasins