A Tale of Two Triangles, Part Two: A Walk In the Woods

In Part One I discussed three things needed to establish an ethics baseline: (1) your center of moments; (2) the full expression of the Golden Rule; and (3) what it means to Live Well Together.

In this section I will introduce you to the Fraud Triangle. I will argue that the Fraud Triangle can be used in many more situations than how it is typically used today. As you will see, the Fraud Triangle is in many ways the Human Triangle.

What is the Fraud Triangle?

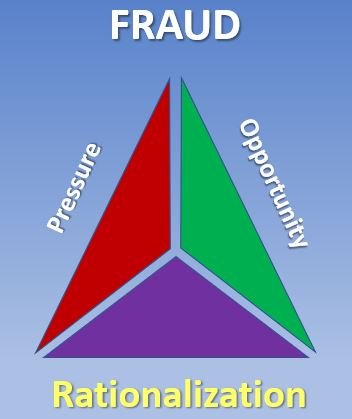

If you search on the Internet, you’ll find a lot of illustrations similar to this:

I’ve deliberately emphasized Rationalization. You’ll see why soon.

Certified Fraud Examiners use this Triangle to illustrate how otherwise “good” people commit financial fraud. Two conditions must exist.

First, there must be some form of financial pressure. This can be anything from unexpected expenses to an overwhelming desire to live beyond one’s means (1). Pressure is what causes people to consider doing something they wouldn’t ordinarily do — to, in effect, “break the rules.” The stronger the pressure, the greater the inclination can be.

Second, there needs to be opportunity. For financial fraud, opportunity means access, or privilege. It’s generally granted one of two ways — through trust, or through negligence. If you are entrusted with access – or, as we say in information security, are granted privileged access – that means you are expected to handle financial matters according to the rules. If you gain access through negligence, it means either that controls which should be in place are not, or that people are either too busy, haven’t thought through, or are too casual about providing you access.

Another way to think of opportunity is temptation.

So now we have both pressure and temptation. What happens next?

For many people, “next” is where your sense of ethics prevails. You decide against violating trust or taking advantage of carelessness. You do your job and solve your financial problems the harder but more honest way.

But for some, “next” is a series of internal conversations. These conversations are where you wear yourself down. You argue that while what you are about to do may seem wrong in the law’s eyes, if people only knew your situation, they would understand why you are committing yourself to action. You’ll only do it once, you say.

This is rationalization before the act. I call it rationalization, part one. Part two is after the act, and part two does two things — it justifies what you have just done; and it paves the way for you to do it again.

And so it goes. It’s why people who commit financial fraud often do it over and over again. Each time it gets a little easier. Each time you feel a little more invincible. You ignore that warning voice that says either Stop Now or Put It Back. After all, you’re clever. You’ll never get caught. Until, of course, you are.

This is a standard portrait of financial fraud, explained by the Fraud Triangle. But I want to go further.

For this, we must take a walk in the woods…

Are you in the woods? Good. Hopefully, there are no mosquitoes. Look around. You might see a squirrel or two. You might hear insects buzzing. You’ll almost certainly hear bird songs — more accurately, territorial war cries — or alarms. And you’ll certainly see trees of all sizes: saplings struggling to punch through the canopy; full-grown tree trunks wreathed in grape, Virginia creeper or (be careful) poison ivy; and scrub trees like chokecherry and redbud. (This is a Michigan woodland, by the way.) Lower down, you’ll see fungi — that strange and wonderful not-plant, not-animal class of living things. Beneath your feet, more than half of the life of the forest teems underground: a vast, largely unexplored network of resource exchange and communication.

I brought you here to show you that all of nature operates according to a triangle similar to the Fraud Triangle. Here is the Nature Triangle:

All of nature — squirrels gathering nuts or chasing mates; birds declaring territory; bees gathering nectar; vines climbing tree trunks to find light; plants elbowing each other aside for space — all of nature is under pressure. But when opportunity presents itself, nature simply acts.

Picture a red-tailed hawk perched on a dead limb of an oak, scanning the field below for signs of life, and then spying a squirrel. I don’t know what that hawk is thinking, but I’m pretty sure it’s not this: “I wish I didn’t have to do what I’m about to do, but I’m hungry and that squirrel will regrettably have to lose its life.” Mission accomplished and squirrel dispatched, I’m also pretty sure that the hawk isn’t reflecting: “It’s too bad, really. I didn’t want to kill that squirrel. But if I hadn’t, I would have starved, and my eyas, too." (2)

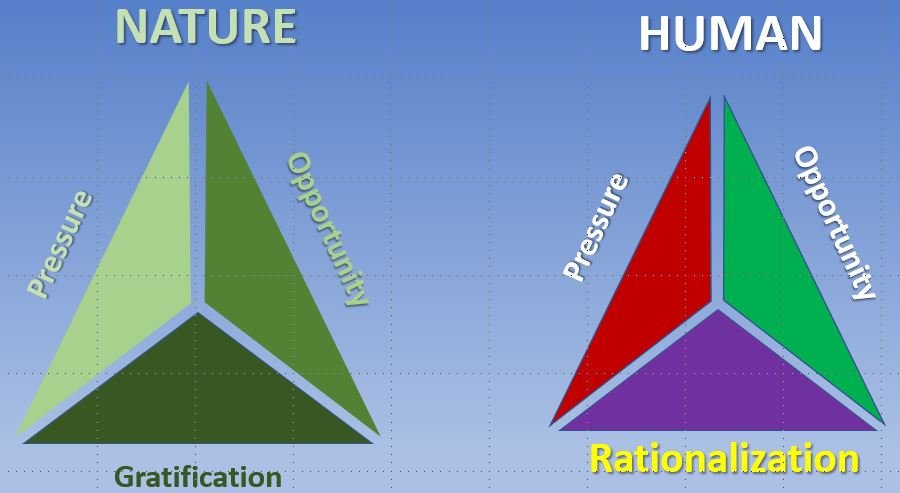

What this teaches us is that the triangle governing nature and the triangle governing humans are nearly identical. I like to refer to the Fraud Triangle as the Human Triangle, because when you think about it, you can generalize the Fraud Triangle to cover much of human activity. Here are the two Triangles, side by side:

As you can see, the only thing that separates the Human (Fraud) from the Nature Triangle is Rationalization. Only humans rationalize. Only humans contemplate an action ahead of time with a “should I or shouldn’t I” mindset, often based upon a set of social constraints — whether that action is as banal as deciding to eat the wrong food or as significant as defrauding a company or deciding on the extermination of a people in the name of ethnic cleansing. To reach this decision, we humans travel down corridors of reason, some relatively simple, others more complex and tortuous, overcoming hurdles as we convince ourselves that what we are about to do is necessary, proper, perhaps even right.

This is Rationalization — the most dangerous side of the Human (Fraud) Triangle. It has two components. One, described above, is the mental pathway we travel to justify what we’re about to do. The second, occurring after the fact, is the pathway we travel to justify what we’ve done.

Rationalization is justification for gratification.

In order to defraud someone else, we must first defraud ourselves. We must first convince ourselves of the necessity of what we are about to do.

We’ll explore Rationalization in more detail in the next installment. Stay tuned.

=========================================

(1) I use “overwhelming” to distinguish one’s reaction to this pressure. We all might daydream about living beyond our means — but (hopefully) few of us resort to extraordinary measures like committing financial fraud in order to attain that lifestyle.

(2) “Eyas” is a baby hawk. I didn’t know that before writing this, and I’ll bet you didn’t either. For more on baby hawks, see: https://misfitanimals.com/hawks/baby-hawk/