A Tale of Two Triangles, Part Three: The ”R” Word

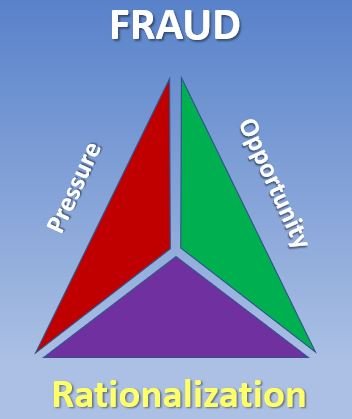

In the previous section, I introduced you to the Fraud Triangle and indicated that it was really in many ways the Human Triangle:

(From now on, I will refer to this Triangle as the Human Triangle.)

We also began exploring “Rationalization” - the least-studied, most-dangerous side of this Triangle. Here’s what I mean.

As humans, we’re under constant pressure. What distinguishes us from the rest of the natural world is the kinds of pressures we’re under. Beyond food, clothing, shelter, procreation, and the basic communications required to secure these, our remaining pressures are either self-inflicted or a product of our social interactions and obligations. You’re probably facing one or more of the incomplete list of pressures shown here, and you could probably name some more:

In the Human Triangle, opportunities are the means by which these pressures can be relieved. Some of these are socially acceptable and legal, while others are not.

Suppose you are in debt. I sympathize, having been there myself — debt can feel crushing, especially if you are on the wrong side of credit card debt, a victim of the wide gulf between the interest you can earn from your bank account and the interest charged for your credit debt. However you got there, the mountain can seem insurmountable. But it can be climbed — legally — through a combination of spending and payment discipline. Some don’t have patience for that, and they begin looking for an easier way out.

Here’s a list of more questionable opportunities of all kinds; note they are not limited to financial:

In our burdened-by-debt example: Suppose you’re in debt and caring for Mom. Further, you are legally authorized to manage her accounts. Day in and day out, you pay for assisted living, doctor visits, medications. You act as patient advocate, you study meds to understand their interactions, you work with (and sometimes against) facility staff, you are there for the occasional trip to ER — on and on. Your life is on hold, while other family members just go about their daily routines. The deck seems stacked against you, and on top of that, you’re in debt.

And there’s Mom’s bank account.

Recall from the first installment in this exploration the three components that help define ethical behavior — your center of moments, the Golden Rule, and living well together. One or more of these may cross your mind at this point, when your finger is figuratively poised over the “Should I / Shouldn’t I” button. Now what?

Fraud takes many forms, not all of which are obviously financial. You are tempted by an attractive member of the opposite sex. You are frustrated in your position, and to gain status you could publish groundbreaking scientific results, if only the numbers were oriented more toward your experimental bias. Your high-school physics teacher unfairly gave you a low grade. All your cool friends are having sex or using certain drugs, or both, and you want to fit in.

To paraphrase Carl Sandburg, fraud creeps in on little cat feet (1). Sometimes it’s as simple as cheating on your diet. Other times, it’s convincing yourself that it’s OK to take your nation to war.

Taking that next step, to seize one of these less-than-ethical, often distasteful, sometimes illegal opportunities, requires you to silence whatever internal protests you may be feeling. You must first hoodwink yourself before you can go about hoodwinking others.

Put simply, you must rationalize what you are about to do. Remember, rationalization is justification for gratification.

Let’s turn to one of the darker paths in human existence: addiction.

I’ll hazard a guess here: Most (if not all) of us are passionate about something. I’m passionate about — one could say, addicted to — writing. But it’s when the object of our passion begins to dominate us that we run into trouble. We may fail to apprehend the moment when what we thought we controlled is really controlling us.

Many of you have seen J.R.R. Tolkien’s epic, “The Lord of the Rings” movie trilogy. Some of you may have read the original works. For those unfamiliar with the story, it revolves around a ring of power whose addictive powers are so great, it will end up possessing those who attempt to possess it. That’s far too simple, I realize. But we actually first encounter the Ring far earlier, in “The Hobbit,” and Tolkien describes its hold on the creature Gollum thus:

In his hiding place he kept a few wretched oddments, and one very beautiful thing… a golden ring… a ring of power….

Gollum used to wear it at first, till it tired him; and then he kept it in a pouch next to his skin, till it galled him; and now usually he hid it in a hole in the rock on his island, and he was always going back to look at it…

… he put it on, when he could not bear to be parted from it any longer… for he would be safe…

“Riddles in the Dark,” The Hobbit, 1939

Addiction overpowers you, even as you fool yourself into thinking you have control over it. Whether it’s drugs or alcohol or anything else, the messaging is frequently the same:

I’ll only do it this once

I’m not as bad as those other folks

I only take one kind of drug

I can control this

Sadly, those suffering from addiction take that last statement to heart. It is the ultimate defrauding statement. it permits the addict to continue down a path that all too often ends either in a devastating loss (friends, family, job, etc.) that forces realization of the truth — or, tragically, in death.

The dark side of rationalization isn’t limited to addiction. The FBI has done considerable work on a phenomenon they call the “pathway to violence.” This seeks to explain the journey someone makes from operating inside society’s norms to pathological behavior. How does someone go from student to school shooter? All along this pathway, the FBI describes reinforcing agents, such as violent websites or hate-filled blogs. A particularly chilling example is the Violence Coach — a person (one could say Influencer), who has gained the trust of this troubled target and, through repeated encounters, encourages and validates violence against others.

The Human Triangle can be used to illustrate this journey. In this case, the pressure an individual feels can be that of needing to fit in, to be accepted. When this need is unmet, the individual feels isolated, wronged, and angry. Information on the Web stokes this anger, and it doesn’t help to have social media business models that profit from offering up fear-driven click bait. The individual feels unbalanced with respect to the rest of society, and looks for a means of restoring that balance, of settling that score, of getting even. Weapons become the great equalizer. If present, a Violence Coach reinforces the rationalization that is going on, encouraging a solution achieved via the annihilation of others.

When the deed — say, a mass shooting — is done, victims’ families will cry out, and politicians may amplify, the need for gun control. Both sides of the furious debate that follows will no doubt have used rationalization to achieve — and reinforce — their positions. I will not comment further on the need for balancing gun laws and Constitutionally-guaranteed freedoms, other than this: The pathway to violence does not need the web, Violence Coaches or high-powered modern rifles. Consider that the single deadliest school attack in US history occurred nearly a hundred years ago, in tiny Bath, Michigan. The weapon of choice? Dynamite. The pathway? An all-too-familiar sense of a grudge nursed down a corridor of hatred, until elementary school children become nothing more than objects to be destroyed along with a school that was the symbol of one deranged person’s view of what’s not right in the world. As though dynamite and slaughter would somehow fix that. (2)

I don’t need to explain here how rationalization leads to cases of classic fraud, either by individuals or by organizations. Belief that the end somehow justifies the means, however illegal those means may be, is what causes the tarnishing of company reputations, whether it’s Wells Fargo for cross-selling consumer products, or Volkswagen for fudging diesel emissions numbers. It’s impossible to over-emphasize tone at the top in these situations: the shadow cast by leadership creates the atmosphere I call “Triangles all the way down,” in which “small r” rationalizations are greased by decisions taken at the top, sending a signal of empowerment through the ranks, ultimately allowing people to justify what they do based in part because of pressure and encouragement from above. Far easier (and often understandable) to say, “I needed to keep my job,” or “I was just following orders” than to face the consequences of small decisions contributing to a larger, fraudulent whole. Rationalization is the tool of choice here, and it’s the same tool whether used to justify altering test numbers or choosing which prisoners will go to the camp and which to the gas chamber. Our greatest evils may be designed at the top; they are built, brick by brick, on the individual rationalizations of people, willingly or unwillingly, adhering to that design.

I’m ending this rumination here, on this dark note. It’s also time to reflect on the subtleties of this dangerous yet ambivalent word, rationalization, to become aware of how it plays into not only justification for actions dispassionately understood as unethical, immoral, or illegal, but also to explain visions of nobler things. After all, consider the flipside of the Human Triangle: how humans can respond to pressures such as social inequities, using opportunities such as new technologies or innovative social designs, rationalizing their investment decisions by painting a picture of a new and better world.

In the next essay, we’ll return to Rationalization, to see how it creates Corridors of Reason that can ultimately divide us from each other.

=======================================

(1) Sandburg’s famous poem is tiny – you can find it here – but I’ll just quote it entirely:

“The fog comes

on little cat feet.

It sits looking

over harbor and city

on silent haunches

and then moves on.”

(2) This tragedy occurred in Bath, Michigan, on May 18, 1927 and ranks as among the most heinous acts perpetrated by a single individual in the history of the country: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bath_School_disaster

An excerpt from this illustrates what we’ve been exploring: “Kehoe, the 55-year-old school board treasurer, was angered by increased taxes and his defeat in the April 5, 1926, election for township clerk. It was thought by locals that he planned his "murderous revenge" following this public defeat. Kehoe had a reputation for being difficult, on the school board and in personal dealings. In addition, he was notified in June 1926 that his mortgage was going to be foreclosed upon. For much of the next year, Kehoe purchased explosives and secretly hid them on his property and under the school.”

In addition, Kehoe murdered his wife and then committed suicide by blowing up his truck near the school. He illustrated both a deranged moral compass and a twisted use of the Golden Rule. He did unto himself what he had done unto others. He failed the third test of the ethical framework — that of Living Well Together.