A Tale of Two Triangles, Part Four: The “R” Word, Again

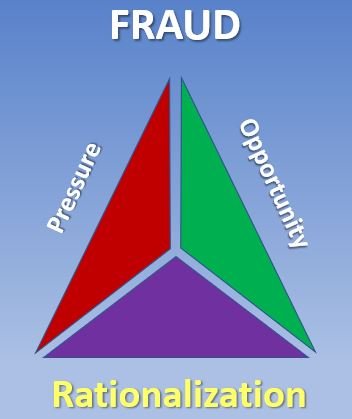

Let’s return to the Fraud - or Human - Triangle and it’s most challenging side, Rationalization.

We now know that Rationalization is Justification for Gratification. We also know how deeply personal and idiosyncratic such rationalization can be.

The mental and moral distance I must traverse before I can actually push the Fraud button is likely different from yours. It stems not only from my personal experiences and the information (or misinformation) to which I’ve been exposed, but also from my upbringing, the values of my parents and other authority figures, my birth order and sibling relations, peers, my socio-economic environment, what ethnic groups may have shaped the family — on and on.

My Center of Moments is different from yours, and the small, still voice I hear may well choose different words than yours. We may both read Hillel the Elder’s words and the words of the second half of the Golden Rule but interpret them differently. Similarly, my notion of “living well together” likely has different contours than yours, different guardrails, moral and ethical boundaries. And all stemming from the notion that while we share a host of common features inherent in our basic humanity, still we are uniquely shaped from before birth and perpetually throughout our lives.

It’s against this very human, very personal backdrop that we’ll finish this exploration of rationalization. We’ll examine its pervasiveness in shaping how we see the world, how it lurks behind the fact that I can see the January 6 events one way, while you may see the same events another way.

I begin with an illustration.

This is Salvador Dali’s famous painting, “Soft Construction with Boiled Beans.” Created in 1936, it is generally thought to be Dali’s representation of Spain tearing itself apart on the eve of the Spanish Civil War. (1) What I find particularly striking about this painting is both the pain and determination the central figure demonstrates. This is a creature hell-bent on tearing itself apart, never mind the pain or the consequences. A powerful symbol indeed for a nation descending into civil war.

You can hardly turn anywhere these days in the news without encountering yet another article bemoaning how America (or Europe, for that matter) is becoming more and more polarized. Dali’s painting seems to describe our situation today. While there are many reasons for this (2), I want to focus on the role rationalization plays in this polarization. To do this, we’ll return to the woods.

Imagine you are starting your walk through the forest, your friend by your side. Shortly after you enter the woods, the path forks. You think one fork looks more inviting; your friend chooses the other. You agree to take these separate paths and meet on the other side, to share what you’ve seen.

You begin. Very quickly, the underbrush surrounds you. You can no longer see your friend. You are alone. As you continue walking, there are side paths that open up. Some of these might lead to your friend’s path. However, none of these look interesting to you; in fact, they seem to be vaguely threatening. There are also side paths that branch off from your main path but seem to head in the same general direction. You take a few of these, and they always rejoin your main path.

Eventually, you reach the other side of the woods. You scan the forest edge, looking for your friend. At first, you see nothing. Finally, though, your friend emerges at a spot so far from you, they appear to be no more than a speck. Moreover, there are now rocks, ravines, rivers and other barriers between you and your friend, making your ability to connect physically with your friend all but impossible. So you call your friend on your cellphone and ask them to describe what they’ve seen.

Listening to the description, you’re astounded: it’s as though your friend hasn’t walked in the same woods at all. You describe what you’ve seen, and your friend is astounded. These aren’t the same woods; in fact, your friend accuses you of not having walked in the woods at all, that you’re lying, making up stories of what you’ve seen. The more you try to suggest you have indeed seen beautiful flowers, shrubs, trees, animals, the more your friend insists it’s not so. You begin to argue. How can they have seen what they insist they saw? They couldn’t possibly walk in the woods and see those things!

Bitter, you abruptly disconnect. You’ve lost your friend.

What happened?

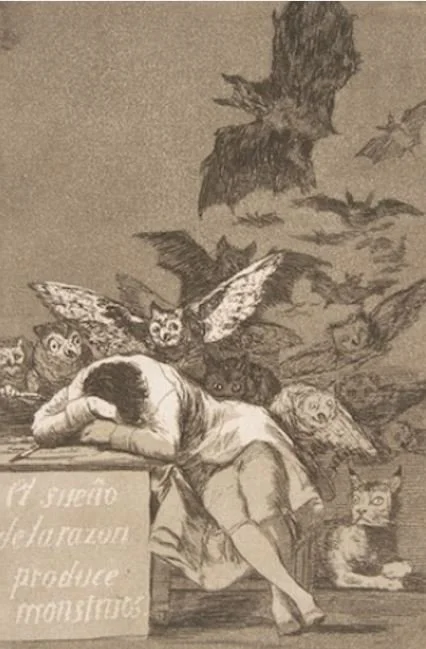

To understand the metaphor of this walk in the woods, we need to look at rationalization’s close cousin: reason. Take a look at this drawing:

Francesco de Goya, another Spanish master, lived a couple of hundred years before Dali. The caption, translated from the Spanish, reads, “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters.” Like Dali, Goya witnessed the atrocities that so often accompany civil unrest. (3)

At first glance, it’s easy to interpret what Goya is conveying in this sketch as what happens to people and societies when reason is abandoned. That’s certainly how I interpreted this sketch, when I first encountered it as a young adult. Back then, as I was learning to appreciate the powers of reason, it was easy to believe that if I abandoned this tool, monsters would emerge. Returning briefly to our walk-in-the-woods partner, it’s easy to imagine an argument that concludes, “You’re being unreasonable!” “No, you are!”

Well, both of us can’t be unreasonable. Or can we?

Or is it possible that we’re both being reasonable?

An equally compelling interpretation of the sketch is that Goya is demonstrating what happens when we use reason to define our world view — that it is the sleep brought about by reason that produces the monsters of our own thinking. (4) The sleep of reason compels us to follow our thought down what I call a corridor of reason — a path reinforced by arguments similar to our own (today we call these “echo chambers”), accompanied by rejection of those arguments that don’t fit our world view. Remember our walk in the woods? We rejected paths that suggested a bridge toward our friend’s path — the other point of view — in favor of continuing on our own path.

We reinforce our world view through reason. We reject other points of view — indeed, we can see these as hostile and threatening. Subject both to the confines and to the reinforcing elements of our individual reason, we walk separate paths through the woods.. This is how we can view the events of January 6 as being either a violent attempt to overthrow the government and undermine our democracy, or a desperate attempt to reject the evil machinery of a pervasive, deep state and so regain our democracy. Which view is correct? Why?

Returning to the Human Triangle, we might ask, what is the pressure we’re under? And what is the opportunity? An event as significant as January 6 has complex roots and therefore does not admit of a simple explanation, just as the Great Depression of 1929 - 1939 has many factors and therefore multiple theories of cause and effect. But perhaps we can offer some conjectures.

For pressure, we might turn to the inequalities and uncertainties of life, the desire for order and predictability — that we will have jobs, clean air and water, decent education for our children, and so on. Not that any of this is guaranteed, but these are all pressures weighing upon us. And because we are a diverse people — urban and rural; know what’s and know how’s; progressives championing causes and conservatives watching costs; races, genders, religions, ages, on and on — different pressures have different emphases. Those who have seen factories close up, jobs move away, and small towns die (5) will view globalization far differently than those riding the cusp of a new tech that may end up swallowing the careers of its creators. (6)

For those who decided to march on the Capitol, the pressures they feel may be similar to pressures felt by the disenfranchised and abandoned at any time in history, a sense that technology, events and politics have passed them by, a sense of despair and desperation, that whatever system is supposedly working, it is not working for them. The Jan 6 call to action is given by someone they see as a leader but whom others see as the ultimate violence coach, concluding months of encouragement with a final push, even if it should mean hanging the Vice President of the United States.

To view this properly we must look not only at the pressures on ordinary people but also on the pressures of those who either would obtain or retain power, which is what the heretofore peaceful transfer of the authority of the presidential office has been about. For those retaining power, the pressures might well be the need to remain in office to avoid legal actions, to avoid diminishing power — and, perhaps, deep down, given upbringing and a creation of a specific kind of center of moments — to avoid being cast, not as a killer, but as a loser (7). For those obtaining power, perhaps a thought of stopping this existential threat to democracy, coupled with a realization, at long last, of a lifelong goal. A surrendering to the desire – some might say temptation – to do good things, but subject to the scrutiny of those who impart other motives to these actions, especially if they should have, as is so frequent when strategy is implemented, unexpected consequences. (8)

How do we know which is more true? For this, we begin with their words, looking for actions that will affirm (and, if we are brave enough, possibly disprove) their words.

There’s more. To fully understand the extent to which our reasoning may be manipulated, we need to understand the role media plays in all this. We are led to what we think are our own conclusions. These conclusions are reinforced, by the media we choose to follow, which in turn follows us (9). Here we must invoke the Human Triangle once again, this time to better understand the pressure media is under, their profit and competitive advantage opportunities, and their subsequent rationalization.

Using media to manipulate — more gently, “to win hearts and minds” — is as old as human social endeavors. What’s different? What are the new pressures? For one thing, today’s major media has had to respond to our evolving digital world. Gone are the days when established print media physically delivered the news to your doorstep. In those days, the pressure was the scoop, the competition the newspaper across town. It’s too much to go into detail here about the buying up of independent newspapers by conglomerates; suffice it to say that along with this pressure came the pressure of the new digital marketplace, where money is made not by selling papers but by selling clicks. (10)

What drives us to move past a headline may not fundamentally have changed. We are attracted to sensational stories. “If it bleeds, it leads.” (11) This has generally put media in the role of selling sensation. There is a scene in the Disney movie, “Newsies,” set in the Depression era, in which the lead character, a newspaper “newsie” (street seller boy), is selling the news by shouting out an obviously false headline. When confronted by another newsie, he responds, “I’m not lying, I’m just improving the truth.” (12)

In today’s world, money is made through clicks. We are most drawn to what angers and frightens us, not that which makes us merely sad or happy. Media’s pressure — coming from multiple fronts, such as regular journalism, fringe websites, tech giants such as Google and Facebook — compels them to jostle their way to the front of the click line, competing for ever-finer slivers of our attention. When we click, they gain. So their pressure is to deliver that which will make us click, and then to reinforce that by shoving the same kind of information in front of us, so that we’ll click again. Never mind if the content is accurate or up to what is left of journalistic ethics. The Pressure is to compete. We are the Opportunity. And if the information misleads us or takes us down our own corridors of reason, even pathways to violence, so be it. The Rationalization is competition, profit, media survival. Regardless of your political situation, take note of this statement, uttered by CBS CEO Les Moonves in 2016, as Donald Trump’s campaign was getting underway: “It may not be good for America, but it’s damn good for CBS.” The fact that Moonves felt compelled to clarify his statement, passing it off as a joke (13) serves only to prove the point that we often act first and rationalize later.

Thus, echo chambers. Corridors of reason. Walks through the woods that leave some of us to see January 6 as a violent attempt to prevent presidential succession and others to see it as a necessary action to prevent the stealing of government away from the people.

Where does this leave us? Are we doomed to follow our paths to our own suicides, as did the people of Saipan? (14) What can we do?

To answer, I’ll bring in the second triangle in the next section. But before we leave the topic, we should recognize that while rationalization can lead us down some frightening paths, it is also the tool we have for evaluating what we’re reading, seeing, and hearing. First and foremost, we need to slow down. Take the time to examine what’s being said. Hit the interrupt “pause” button if possible. Read to absorb and understand, not just grab and go. Fast information, like fast food, is not healthy in the long run. It may well prove fatal. (15)

Next: What To Do — The Security Triangle viewed a new way.

=========================================

(1) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soft_Construction_with_Boiled_Beans_(Premonition_of_Civil_War)

(2) Among these, in no particular order of importance: (1) increased economic inequality / widening gulf between the ultra-rich and all the rest of America; (2) special interests embodied in deep-pocket lobbying groups drafting legislation that disregards the wishes of voting America in favor of advancing the lobbyists’ corporate agenda; (3) codification of big money as the primary driver in political candidate selection through the Citizens United Supreme Court ruling; (4) a view of corporations as people, which entitles corporations to enjoy the same kind of rights that the Constitution enshrines, even though ordinary people cannot avail themselves of the kinds of privileges and protections corporations enjoy; (5) media of all kinds operating in an intensely competitive model where content value is driven far less by quality and accuracy and far more by appeals to our centers of anger and fear, as these generate more advertising clicks and therefore more money; (6) isolation and (to some) draconian measures intended to protect the population during COVID, resulting in the same kinds of for / against clashes as occurred during the last major pandemic (Spanish Flu, 1918-1920), and whose knock-on effects linger today; (7) you get the idea.

(3) But Goya was far darker. A master portraitist, he also suffered a mysterious illness. Withdrawing from the elite circles in which he was highly regarded, he drew disturbing sketches (Caprices, Disasters of War), reflecting his reaction to the horrors of the Peninsular War (in which France invaded Spain). But these sketches were child’s play compared to his darkest works, the “Black Paintings,” produced when either illness or dementia or both allowed monsters to overrun his canvases — which, for these devastating works, were the walls of his house.

(4) For this interpretation, see — https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/becoming-modern/romanticism/romanticism-in-spain/a/goya-the-sleep-of-reason-produces-monsters

(5) For a great fictional rendering of this, see American Rust by Philipp Meyer (but, apparently, avoid the television series — and why anyone would take a self-contained exposition like the novel and decide to serialize it is, frankly, beyond me).

(6) As in just about anything that comes along, when you think about it, the latest being GenAI. This simply underscores the need for people in an ever-changing society to adapt like chameleons by learning new skills. Of course, the alternate point of view is that certain bits of progress are inherently evil and must be resisted at all costs. Given history, what we might be able to best guess is that each change — whether climate, technology, social, or some combination — propels us down different and new paths with choices that unfold as a result. So all of creation and development might I suppose be viewed as one long walk through an ever-evolving woods.

(7) Trump’s dad: “There are two kinds of people in the world: killers and losers.” Imagine that as your upbringing. No, wait — some of you reading this will say that he is simply speaking the truth. This is far more difficult than we’d like to think. See: https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/trump-the-bully-how-childhood-military-school-shaped-the-future-president/

(8) Here I’m reminded of a passage early in The Lord of the Rings, in which Frodo offers the Ring of Power to Gandalf. His response: ‘With that power I should have power too great and terrible. And over me the Ring would gain a power still greater and more deadly. … Yet the way of the Ring to my heart is by pity, pity for weakness and the desire of strength to do good. Do not tempt me! I dare not take it, not even to keep it safe, unused. The wish to wield it would be too great for my strength. -- Tolkien, J.R.R.. The Lord Of The Rings: One Volume (p. 61). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.

(9 ) Or vice versa. Media may follow us first. Either way, once the handshake is established, the fun begins. For a full and detailed exploration of this, see Surveillance Capitalism, by Shoshana Zuboff.

(10) Even this isn’t the full story. In Civil War times, newspapers belonged (in a sense) to one party or the other, and the information you gleaned from them was just as subject to manipulation then as it is today. So we’d do well not to confuse the medium for the approach, which remains the same.

(11) I spent just enough time looking this up to realize that not only is it basically ubiquitous and difficult to trace to any one individual, it describes how we have responded to media since — well, since we’ve been creating stories.

(12 ) “Newsies” was an improbable hit, a Disney feel-good film about tough news kids growing up on city streets and taking on the media establishment by going on strike. On top of that, it was a musical. Who did those anymore? Of course, it bombed. But I, like many others, found the combination of story, great music and energetic dance to be captivating. (It helped that my dad had been a Newsie.) It was resurrected as a musical by the same name and had quite a successful Broadway run. You never know how good art will “out.” See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Newsies

(13 ) Here’s the rationalization. You’d think a media executive would understand that it’s the initial words that stick, not the walking back or doubling down or whatever else we call it. Then again, maybe he did realize it, and this is just lip service: https://www.politico.com/blogs/on-media/2016/10/cbs-ceo-les-moonves-clarifies-donald-trump-good-for-cbs-comment-229996

(14) I treat this in detail in the essay by the same name: https://www.davidsoubly.net/citizen-squirrel/saipan

(15) Bruce Schneier introduced me to the notion of the Internet as an interruption service in his book, Data and Goliath. And for more on our loss of judgment due to the constant flow of interruptions that prevent us from reading and absorbing, see Nicholas Carr’s The Shallows. For more on slowing down and taking stock, see my essay, “Stop, Look and Listen” — https://www.davidsoubly.net/citizen-squirrel/stop-look-and-listen